Digital Zeitgeist – Why Does The United Kingdom Have The Highest Inflation Rate Among The G7 Countries And Is Brexit A Factor

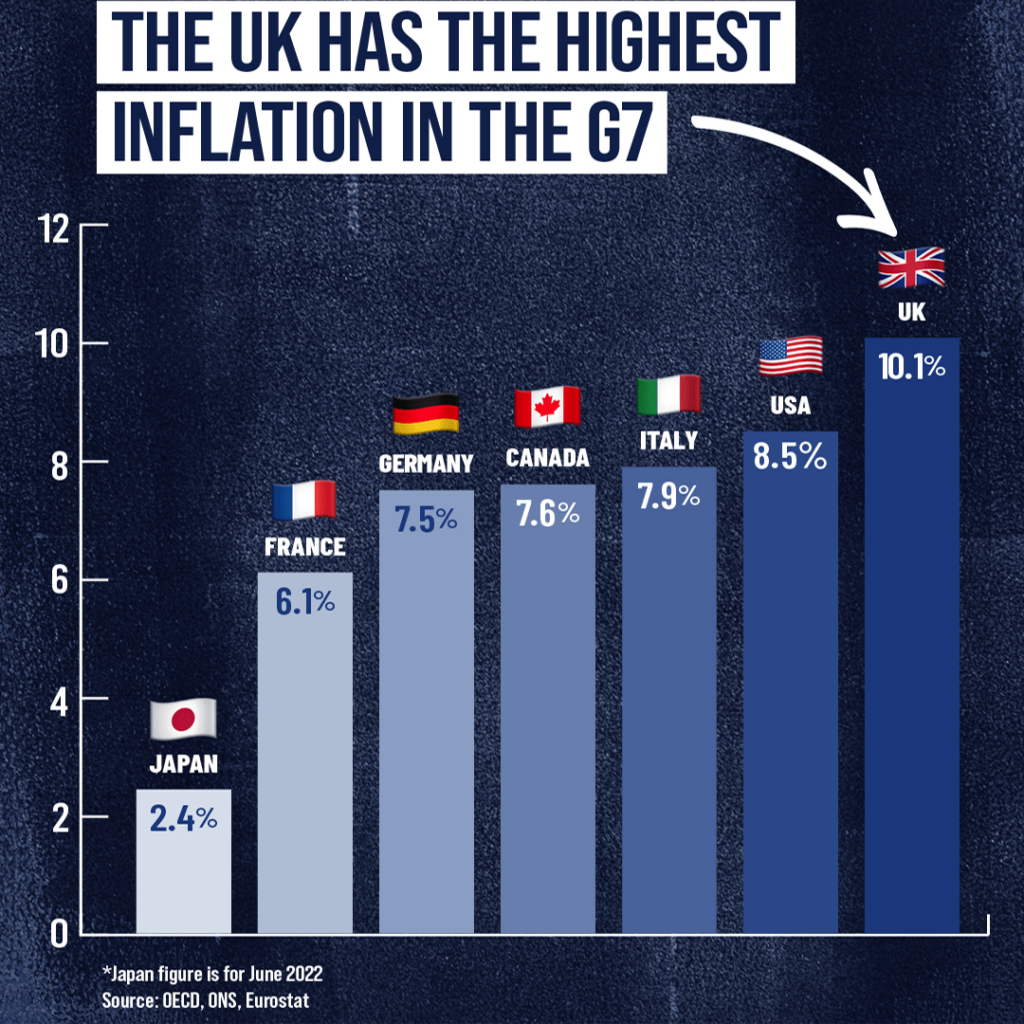

With the unexpected rise in prices that occurred last month, the United Kingdom now has the highest rate of inflation in the G7, making it the only country in the group of advanced economies with a figure in the double digits.

Several economists have hypothesised that Brexit is having an effect because the United Kingdom stands out as an outlier on the world stage.

International comparisons

The headline inflation rate in the UK is much greater than the inflation rate in other countries. Inflation in the eurozone dropped to 8.5% in February, down from a top of 10.6% in October, while inflation in the United States slipped to 6% last month, a dip from a high of 9.1% in the summer of last year.

On the other hand, it is not a completely consistent image. France and Germany both had higher rates of inflation in the most recent month, although the overall rate of inflation for the EU27 fell from 10% to 9.9%. In the eurozone, economists had anticipated a larger drop in the unemployment rate, from 8.6% in January to 8.2% in March. On the other hand, the pressure from increasing food costs — the same factor that was responsible for the shocking surge in the UK – led to a surprisingly tiny decline.

Core inflation, which is used by central bankers because it excludes energy and food, providing a clearer picture of underlying pressures, rose by more than expected in both the Eurozone and the United Kingdom. Core inflation rose from 5.8% in January to 6.2% in February for the United Kingdom, while core inflation rose from 5.3% to 5.6% for the European Union.

There are various aspects of an economy that might cause inflation to grow or decrease at certain periods, which may not be repeated in other countries. These aspects may not be as prevalent in other countries. One such instance is the price limit imposed by Ofgem in the United Kingdom, which results in cliff edges for the fluctuation of energy prices. For this reason, economists anticipate that the rate of inflation in the United Kingdom will drop significantly in April, as it will be compared to the enormous increase of 54% in the Ofgem cap one year earlier.

While inflation may be volatile from month to month, making it difficult to determine an overall trend and making it more difficult to single out Brexit as a driving cause, there are still a number of reasons why the United Kingdom could be in a worse position than other countries.

Supply chains

Because of Brexit, the delivery times and prices of imports into the UK have increased, which is a factor that is likely to be passed on to customers in the stores.

Because of widespread severe shortages and rationing in the UK in the previous month, the cost of cucumbers, tomatoes, and salad surged sharply in February, contributing in part to the unexpectedly high level of inflation that month. Several experts referred to Brexit as the cause of the shortages, given that there are no empty shelves in countries that are members of the EU. Nevertheless, other experts blamed the shortages on exceptionally cold weather that affected crops in southern Spain and Morocco.

Justin King, the former Sainsbury’s chief executive, said the UK food sector had been “significantly disrupted” by leaving the EU, while producers in the bloc warned Britain had slipped down the pecking order for deliveries when supplies are tight.

According to findings published by the London School of Economics, the price of food in the United Kingdom would increase by around £6 billion over the next two years, ending in 2021.

However, there are also domestic reasons. Growers blame powerful British supermarkets for driving down the prices they are paid, limiting supply, as well as the government’s approach to subsidising food production. Economists also say soaring energy bills are the biggest driver of food costs, given the impact on everything from fertiliser, tractor diesel and lorry shipments, to keeping bakery ovens fired and food factory production lines rolling.

Worker shortages

In addition to disruptions in supply chains and rising energy prices, labour rates also have an effect. Workers are seeking greater pay settlements from employers as a reaction to the inflation shock. At the same time, a scarcity of available labour in many areas of the economy is pressuring corporations to provide higher compensation in order to either attract new employees or keep the ones they already have.

There is a possibility that stricter immigration rules brought about by Brexit are contributing to the problem. This is especially possible in roles that are typically lower skilled and pay less, such as those found in the hospitality and food production industries, where employers used to be able to rely more on EU workers coming to Britain.

The decrease in the number of people moving to the United Kingdom from other countries within the European Union (EU) has been more than offset by the increase in the number of people moving to the United Kingdom from countries outside of the EU.

Despite this, research conducted by the Centre for European Reform and UK in a Changing Europe suggests that Brexit could have still resulted in a shortage of 330,000 people in the UK labour force. This is the case even after considering how the workforce might have appeared if the United Kingdom had remained a member of the EU.

The lack of available staff to fill near-record job vacancies could force employers to increase wages, which has the potential to fuel inflation even further. This is due to the fact that older workers are leaving the labour market entirely, as well as the record levels of long-term sickness among the population of working age in the UK.

online sources: theguardian.com, cer.eu