Why Are UK Bond Yields Rising and Why Does it Matter?

Borrowing Rates in the United Kingdom Have Climbed as Investors Become Pessimistic About the Economy’s Prospects

Kwasi Kwarteng’s tax-cutting mini-budget caused the pound to plummet and the UK’s borrowing rates to rise.

Sterling sank to its lowest level against the dollar in history at one point on Monday. According to Deutsche Bank, the UK’s borrowing rates for 10-year government bonds have climbed the greatest in a five-day period since 1976, when Britain turned to the IMF for a bailout.

What are bond yields?

A bond is a loan made by investors to a bond issuer. When governments, corporations, and other organisations need to generate funds, they issue them. The bond market is the world’s largest securities market, valuing more than $100 trillion (£93 trillion). Government bonds in the United Kingdom are often known as gilts.

Bond yields show the amount of money an investor receives as a percentage of the debt’s current price. Bond yields rise when bond prices decline. The yield is also known as an interest rate or the “cost of borrowing” for an issuer.

Rising bond yields indicate a lack of investor appetite to hold debt since purchasers demand a lower price to buy them.

What’s causing the rise in yields?

Borrowing rates in the United Kingdom have risen as investors become pessimistic about the economy and state finances. 10-year bond yields have surged beyond 4%, the highest level since the 2008 financial crisis and more than quadruple the 1.3% rate at the start of the year.

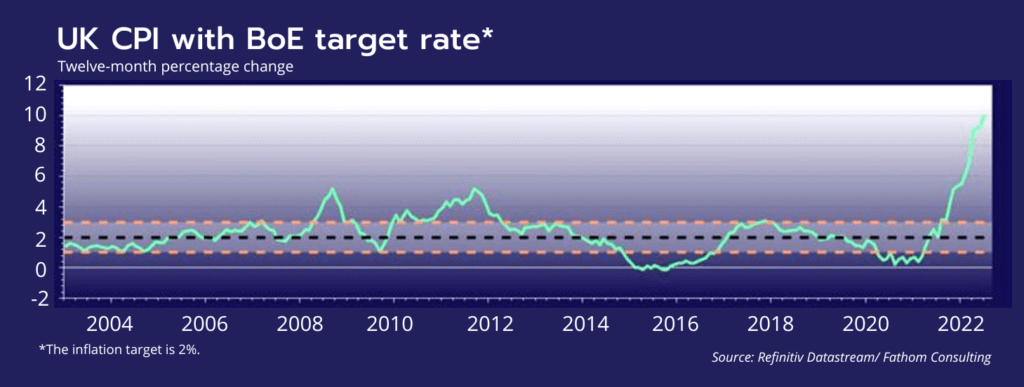

Bond yields in industrialised nations have climbed this year as rising inflation, worsened by Russia’s war in Ukraine, weighs on the global economy.

The UK, on the other hand, has seen a more severe sell-off, evoking analogies to an emerging market economy such as Mexico rather than the world’s fifth biggest. There are three main causes behind this.

First, Kwarteng’s mini-budget is widely seen as the primary catalyst for the current increase, following the chancellor’s announcement of £45 billion in unfunded tax cuts.

An additional £72.4 billion in debt sales are now planned for the current fiscal year alone to finance more borrowing to pay for tax cuts. In addition, the Bank of England intends to sell around £40 billion in bonds over the next year in order to wind down its quantitative easing (money printing) programme.

Deutsche Bank anticipates gilt sales to exceed £250 billion this fiscal year and next, the largest funding demand since at least the 1990s. This is likely to prompt investors to seek lower prices – implying greater yields – in order to purchase such large volumes.

Second, because of its reliance on gas, the British economy is experiencing a greater inflationary shock than other countries. Brexit is also having an impact on commerce, as the UK has a big negative balance of payments, which means that more money is spent on foreign products, services, and investments than is taken from abroad.

Third, some investors believe the Bank of England is falling behind the curve in combating inflation. The central bank lifted interest rates by 0.5 percentage points to 2.25% last week, compared to the US Federal Reserve’s harder 0.75 percentage point increase.

Kwarteng’s tax cuts and the government’s energy price guarantee are projected to exacerbate already high inflation while doing nothing to boost long-term economic development, putting pressure on the Bank to hike interest rates. Investors anticipate that rates will be raised to around 6% as early as February 2023.

Why does it matter?

Rising borrowing rates will make servicing the government’s obligations more expensive. According to Bank of America analysts, there is a possibility of a “feedback loop,” in which a lower currency leads to greater inflation, a higher bond yield, and more government borrowing.

According to the Resolution Foundation, the jump in rates may add around £14 billion to borrowing by 2026-27, and it comes in the context of a mini-budget that is already expected to increase overall borrowing by more than £400 billion over the following five years.

Households might also be affected hard, wiping out much of the gains from Kwarteng’s tax reduction.

A rise in interest rates above 5% by the Bank of England would have a significant impact on both individuals and businesses, given many consumers have only seen rates close to zero over the last decade.

According to Samuel Tombs, the chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, if mortgage rates climb to 6%, the average family refinancing a two-year fixed-rate mortgage in the first half of 2023 will see a surge in monthly repayments to £1,490 from £863.

Higher borrowing costs might also lead to a dramatic decrease in property values, further straining household budgets and having a negative knock-on effect on the country’s economy.

Online sources: theguardian.com All opinions and views expressed or suggested by the Digital Zeitgeist are not necessarily the same opinions and views held by or suggested by GPM-Invest plus any and all partners, affiliates, parties, or third parties of GPM-Invest. Any type of media distributed by GPM-Invest IS NOT financial advice. Please seek advice from a professional financial advisor